Entering into Cleveland Public Theatre after a long week, we found ourselves listening to Danny Lahood on oud and then stuffing ourselves on shish tawook and hummus and baba ghanoush. It reminded me when I was young, I was told by my grandma Lily, “eat if you love me.” Just last month, I’d been walking the streets of Lebanon, where whole neighborhoods had the scent of my grandmother’s kitchen. I kept wanting to say that I’d come to Lebanon again, but it was the first time in my life I’d ever been able to go. Still, I’d been hearing of it so long that it felt as if I’d been there before.

Entering into Cleveland Public Theatre after a long week, we found ourselves listening to Danny Lahood on oud and then stuffing ourselves on shish tawook and hummus and baba ghanoush. It reminded me when I was young, I was told by my grandma Lily, “eat if you love me.” Just last month, I’d been walking the streets of Lebanon, where whole neighborhoods had the scent of my grandmother’s kitchen. I kept wanting to say that I’d come to Lebanon again, but it was the first time in my life I’d ever been able to go. Still, I’d been hearing of it so long that it felt as if I’d been there before.

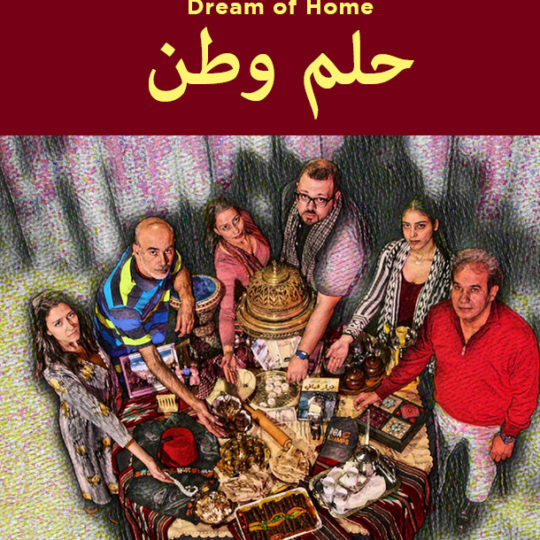

Watching Dream of Home حلم وطن, the performance by Masrah Cleveland Al-Arabi مسرح كليفلاند العربي, an ensemble of Arab American actors, I kept having that feeling of déjà vu—when scenes would cause me to cast back to conversations with my Dad, a proud Lebanese American who wanted to make sure that I knew the traditions, and would carry them forward.

The play begins with the chorus of music that instantly reminded me of Melkite Mass, the lilting tones of musical scales familiar in the Arab world, with the actors singing themselves to the stage. Once the music stopped, the actors shared their names—sometimes in Arabic, sometimes in English, sharing the meanings of the names and where they came from (the play would shift between languages, supertitles for the monolinguals in the audience). Names, for Arabs, reflect not only a couple’s choice, but an entire family’s wishes, histories, and traditions.

Though the actors had a variety of stories for how they were named and why, this opening dramatized a consistent theme: the tension between the individual seeking their way in the world and the centripetal force of family, always drawing the individual back into its field. Whether the family is abroad or in America, each Arab American has to contend with the Old Country, the bilad.

The longing for home is exacerbated by an immigrant’s experience of living “between two worlds,” as if in a dream. An early scene shows Haneen Yehya surrounded by swirling figures calling her back home (either by family or hostile Americans), as she tries to make sense of the voices, not sure if she’s awake or dreaming.

Walking the streets of Lebanon, I had a similar feeling, as if I couldn’t believe I was actually there, knowing that I was only there for a short time, and that this intense homecoming would shortly become no more than a dream. The predicament of living in two worlds is that one feels the tug of the other one enough to make it difficult to be in just one place.

That’s intensified in Arab culture, because the call of family is so strong. In another scene between Omar Kurdi and Jamal Julia Boudiab, the sister calls the brother to come home and get married, and tells him that his old flame is still single, and that she has a job. But the brother knows that the economy is still troubled, and that she’s only doing an unpaid internship. He invites the sister to come to America, where there is real economic opportunity. But the sister balks because she doesn’t want to have to start university all over again.

And later, in another scene, when Jamal (called Julia) comes back to Lebanon, she’s overwhelmed by the intensity of family relations, where neighbors barge in at all hours, and everyone leaves the door unlocked. “Julia, you’re different now,” they say. When she complains, they say, “love and affection do not have limits,” but she just wants to have time alone. She has changed, of course. The predicament of the Arab American—indeed, most immigrants—is that they are changed by the journey and the time in America.

And there is fear about what that means for the preservation of one’s culture and tradition. Issam, playing a traditional Arab father (sometimes straight and serious, sometimes comically), engages in a witty translation of Jamal’s wishes and vice versa, as he navigates the new world with his old compass. He fears the new influences of culture and mores, and wants his daughter to live at home and not watching R-rated movies. She wants to be free, and notes that even in the Old Country they don’t have such rules. Their repartee was funny and poignant, as they translated for the audience what the other wanted of them. This scene struck home as so true—how the immigrant family, wanting to preserve home, preserves a bygone version of it, one that actually only partly resembles it.

Though Dream of Home حلم وطن stays away from national politics, it does dramatize the gender politics of Arab life. That parents hold their daughters closer and to stricter rules than their sons. “You have to obey and obey and obey,” one laments. In another scene, a wife is blamed by her husband for their disrespectful son. This gendered interaction is painfully familiar to me.

At key intervals, Abbas Alhilali, who is also a poet, took a turn around the stage, looking like a glorious Arab hippie with long white hair, chanting poems about home. His voice becomes a poetic promise of the possibility of weaving the two worlds together, as does Omar Kurdi’s gloriously beautiful singing.

Toward the end, a fable about “Ahmad and Michel,” two friends who lives take a tragic turn, offers itself as a parable for politics as well. In the end, I personally wished that the political dimension of Arab American life were most explicit, given how pervasive it is both back in the Middle East and here in the United States. It’s surprising that there was no mention of the Syrian Civil War, the invasion of Iraq, or the Palestinian predicament; among my Arab American writing community, these are persistent points of conversation. I hope that future plays by Masrah Cleveland Al-Arabi مسرح كليفلاند العربي would have the courage to delve into those painful subjects as well—not to resolve them, but to deal with the hurt and loss that is more than individual or familial, but national and even international in dimension.

Still, this is the powerful first foray into depicting Arab American life, where Arabs can find themselves depicted as complex human beings, beyond the hurtful caricatures of Orientalism, and Americans can have a seat at the table of the Arab feast.

To read other Everyone’s a Critic reviews, or to post your own review, click here.

CLICK BELOW FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT

Dream of Home حلم وطن

Dream of Home حلم وطن is about how we remember, seek, and create home, celebrating connections to our past heritage and sharing culture with the broader community.